The Bonelli family first came to the West as Mormon pioneers in 1860, 1861. This article is taken from Family Search and was written and submitted by Waldo C. Perkins MD. Daniel and Haigh are the parents of prominent Kingman resident George Albert Bonelli who built the Bonelli House in Kingman.

DANIEL AND ANN HAIGH BONELLI 1

Daniel Bonelli, was born 25 February 1836 in Switzerland and died at Rioville, Nevada, on 20 December 1903, at the age of 67. Described as a “renaissance man” by one historian, his life can now be told with a broader stroke of the pen and with historical accuracy.2 He was Muddy (Moapa) Valley, Nevada’s first permanent pioneer, arriving in 1868 and residing there until his death. A man of many talents Bonelli was known as a great letter writer, a viticulturist (cultivation of grapes especially for the production of wine), and a shrewd entrepreneur.

Rioville, situated at the junction of the Virgin and Colorado Rivers and now covered by the waters of Lake Mead, was half a world away from Bonelli’s birthplace in the village of Bussnang, located in the northern Switzerland Canton of Thurgau, about 20 miles south of the Bodensee (Lake Constance) and the German border. Bonelli’s parents, Hans George and Anna Maria (Mary) Bommeli and their children joined the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in 1854. Following their baptism, Daniel and his brother George changed their names to Bonelli to symbolize that they had become “new persons.”3 Daniel was ordained a priest and placed in charge of the LDS members in Weinfelden, nine in number. As an active and effective missionary Daniel baptized forty of the fifty-six Mormon converts in Switzerland in 1855.4

The sale of the family home and furnishings yielded enough money to provide transportation to Utah for Daniel’s parents and three younger sisters. They journeyed to Liverpool and from there sailed to America on the George Washington, crossed the plains in the Israel Evans’s Handcart Company and arrived in Great Salt Lake City on 11 September 1857.

That fall, Daniel who had been banished from Switzerland for preaching the Gospel, arrived in England in October 1857 to serve as a missionary. In addition to missionary work Daniel wrote nine articles for the Latter-day Saints Millennial Star on such topics as “Language and Its Proper Use,” “Hope,” “Philanthropy,” “Regeneration,” and “Divine Purposes.” The articles reveal that Bonelli, as a young 23-year old had a very good command of the English language and the doctrines of the Mormon Faith.5 Daniel’s brother George and their sister Mary, who had been working as a weaver in Germany, sailed for America in 1859 on the Emerald Isle. Arriving at Castle Garden in New York, too late to travel west they worked and waited in the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn until the following spring when their brother Daniel arrived on the Underwriter. Together the three of them journeyed by rail and river steamboat to Florence, Nebraska, where Daniel joined the James D. Ross Wagon Train6 and his brother and sister joined the Jesse Murphy Wagon Train.

Arriving in the Salt Lake Valley in September of 1860 the three emigrants enjoyed a pleasant reunion with their family members who were living in the Nineteenth Ward where there father had established a successful spinning and weaving business. Both George and Daniel worked at whatever employment they could find. We know that George worked as a shoemaker and also regularly shucked corn for Bishop Edwin D. Wooley of the Thirteenth Ward.7 Little is known about what Daniel did except for secretarial work including secretary of the German Home Mission where he wrote letters for Karl G. Maeser to President Brigham Young.8

It is family tradition that Bonelli served as a private secretary to Brigham Young. However, a detailed search of the Historical Department Journal from the time that Bonelli arrived in Utah until his call to the Southern Utah Mission in late October 1861 does not substantiate this tradition. The journal notes that Richard Bentley, a secretary of Brigham Young, was called on a mission to England and was replaced but Bonelli is not mentioned. Supporting the families position is a letter Bonelli wrote to Brigham Young from Santa Clara in which he concludes, “With sentiments of high esteem and kind regards to . . . the brethren in the office.”9 In another letter to Apostle George A. Smith, Bonelli concludes, “Give my regards to Brothers Woodruff, Long, and Bullock.”10

Just over a year of his arrival in the Salt Lake Valley, Bonelli was called during the October 1861 church conference to lead a group of Swiss Saints to strengthen the Southern Utah Mission and to establish a wine mission in Santa Clara. During the conference, “Brother Daniel Bonelli read the names of the twenty-nine heads of Swiss families who were selected to settle in the southern part of the Territory.” President Brigham Young said, “If the brethren did not choose to volunteer for this mission that the Presidency and Twelve would make the selections and they would expect the brethren to go and stay until they are released.”11

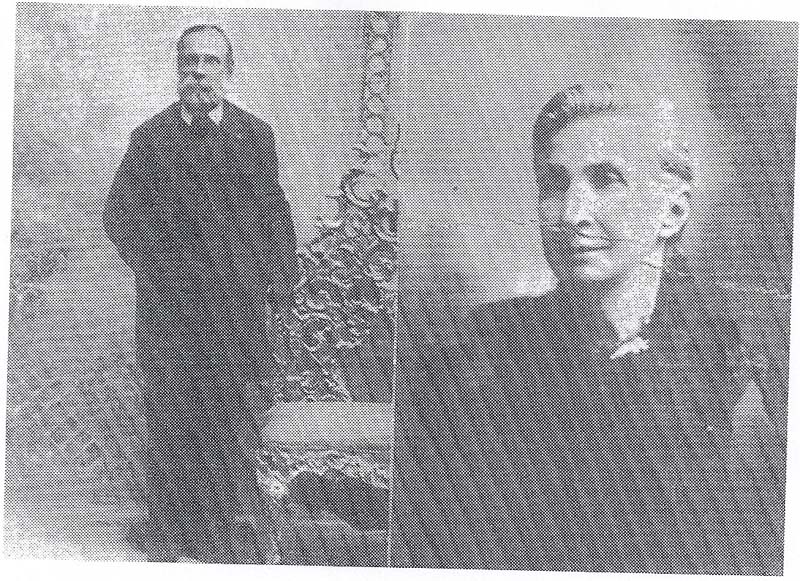

Brigham Young encouraged those about to leave for southern Utah to find companions and be married in the Endowment House. Accordingly, Daniel Bonelli, age 24 and his 26-year-old English friend Ann Haigh (pictured above) were married in the Endowment House by President Daniel Hanmer Wells on 26 October, 1861. They would become the parents of seven children: Caroline Ann, 1863;12 Daniel Leonard, 1865;13 Mary Isabelle, Belle, 1867;14 George Alfred, 1869,15 Benjamin Franklin or Frank, never married, 1871; Edward, 1873 – died when 10 days old; and Alice Maud, 1874.16

Following a pattern developed in the British Mission, Bonelli would take up his pen at the slightest provocation. During his lifetime he wrote over twenty-eight letters. From these letters we can follow his movements from Santa Clara to Millersburg (Beaver Dam), to St. Thomas and finally to Rioville.

Many of those called to go to Santa Clara were too poor to buy the necessary oxen and wagons; hence the bishops of the various communities along the route were instructed to provide the teams and wagons. While journeying south the Swiss attracted a great deal of attention by their singing and yodeling and general good cheer. In Beaver they provided music and danced on two consecutive nights.17 Arriving at Fort Clara on 28 November they joined the twenty English families of Fort Clara and settled south and east of them. Bonelli, as the presiding elder dedicated the land which had been selected for the Swiss Saints, following which lots were apportioned by a lottery.

Less than two months later a great flood roared down the Santa Clara Creek. Bonelli wrote to Brigham Young on Sunday, 19 January 1862 explaining that “at three o’clock this morning the last vestige of the fort, the schoolhouse and seven other houses above the fort had disappeared and in their place roar now the wild torrents of the river, still widening by the continued fall of both banks. Dr. Dodge’s [Walter E.] nursery is also gone along with many other gardens and orchards.”18

The early history of Santa Clara has been told many times and need not be repeated.19 Suffice to say that two months after the flood the industrious Swiss had again built dams, dug irrigation ditches and now had planted gardens, grain, cotton, and vineyards and fruit trees.

The Deseret News of 29 May 1864 published a letter from Bonelli in which he stated that the Swiss population in Santa Clara, now the majority, was “endeavoring to cultivate the grape to the extent that their circumstances and means permitted.” They had learned that the California grape was not hardy enough to withstand the Dixie winter and they were trying to propagate the Isabella and Muscatine varieties. He then made this optimistically bold statement: “I have no doubt that this country will prove as good a wine growing district as the south of France and Italy.”20

In 1865 Bonelli was called to help settle Millersburg (now Beaver Dam), forty miles southwest of St. George. With characteristic energy and optimism, he went to work and soon had a nursery, vineyards, and fruit trees under cultivation and ready to bear fruit. Two years later in 1867, he wrote, “There is no climatic reason why we should not raise the fig, the lemon, olive, pomegranate, and perhaps even the orange. We have imported the best raisin and some grapes of Spain, Portugal, France, Hungary and the Canary Islands and we only require the time they need to come into full bearing to prove [to] Utah that we can raise as good grapes as ever graced the sunny hills of Spain or the hills of Hungary.”21 Bonelli and the Swiss had crops with promise of ample fruiting when on Christmas Eve of 1867 a disastrous flood wiped out all of their best efforts. Bonelli lamented “that young orchards and vineyards, with good promise of ample fruiting the present season, the first of their full bearing have taken passage towards the Pacific.”

Millersburg was abandoned after the flood had destroyed almost everything the Saints had worked for. Bonelli arrived at St. Thomas in the spring of 1868, built a solid five-room adobe house which remained functional until covered by the rising waters of Lake Mead in 1938.

He again planted grapes and other fruits and became one of the biggest boosters of the settlements on the Muddy. In April of 1868 he wrote a lengthy letter to the Deseret News on cotton culture, reflecting an amazing technical expertise.22 Seven weeks later he would write: “. . . After being washed out from the Beaver Dams . . . and having orchard, vineyard and nursery partly freighted gratis to the Gulf of California by the flood, and partly conveyed on wheels to this place, stands again erect with a better vineyard than he had before and a better place, working with more zeal.” He then mentioned the grapes under cultivation, “the Isabella and Catawba of frosty climes . . . the Syrian of the Holy Land and the Perfumed Muscat of Egypt, with the raisin of Hungary, each taking kindly to the soil and thriving better than in their own land . . . St. Thomas can now boast the best collection of varieties to be found on the Pacific slope, excepting perhaps, one in Sonoma County, California.”

He also wrote that Colonel Alden A.M. Jackson, who had resided in San Bernardino for many years, was on his way to St. George to gather with the Saints.23 Then he continued, “Southern Utah is largely indebted to him and his lady for the introduction of the choicest seeds and scions (cuttings) that could be procured in California for many years.” Yet Bonelli with direct bluntness, points out that fruit will be a doubtful crop in the Muddy Valley because many settlers leave after wheat harvest to go north, leaving their fruit trees with no care. Only with proper attentions could one expect a bumper crop. He concludes his letter by yearning “for the time when people will not only stay here and labor because they have been required to do so, but because their homes . . . which have been consecrated by their prayers and exalted by their presence . . . [are] reverenced and the God of Israel is adored.”24

Of all the settlements organized by Brigham Young, the Muddy was one of the most difficult. Malaria from the stagnant swamps, insufferable heat (120° in the shade), Indians stealing cattle and causing other problems, settlers called but abandoning after a few months, all combined to make the Muddy extremely challenging. Bonelli was aware that in the eyes of many the Muddy Mission was not a popular one, and he sensed that many called to the Muddy were not happy and were anxious to return to the north. He observed: “The general idea prevailing in Salt Lake about the muddy is that it is a sort of purgatory or place of punishment, something like the Siberia of the Russians or the Algeria of France, a place no one would occupy if not positively required by irresistible authority . . . But with those who are desirous of redeeming the desert land and submitting it to the rule of Jehovah, consecrated by their prayers and improved by their labors, it is very different.”25

In March of 1870, Brigham Young made his only visit to the Muddy and traveled from St. Thomas to the confluence of the Virgin and Colorado Rivers, fully intending to cross the Colorado. Not happy with what he saw, Warren Foote, counselor to James Leithead in the mission, reported: “President Young was very much disappointed, and refused to cross the river. He said ‘if the Gentiles wanted that country they were welcome to it’ . . . it was plain to see that President Young was disappointed in the whole country.”26

That fall, a boundary line dispute was resolved revealing that the Muddy settlements were in Nevada and not in Utah and Arizona. Faced with the payment of back taxes in specie, the Saints voted to abandon the Muddy and all left except Daniel and Ann. Ann was expecting a child and both she and her husband later stated that “they didn’t leave the church, the church left them.” In Santa Clara, five years after the Mormons abandoned the Muddy, Bonelli, was “cut off from the Church for rebellion” on 21 October 1876.27 This action was taken without Bonelli being present. Bonelli “always declared he was a firm believer in the original principles of the Mormon faith . . . I have never claimed any allegiance to the Mormon Church during the past thirteen years aforesaid, nor denied the same previously, but I . . . know that many Mormons . . . are incomparably superior in rectitude and veracity to those who contemptuously berate them.”28

Bonelli discovered mica mines and organized the St. Thomas Mining District and was its recorder until his death. Sometime in 1878 or 1879 he established a ferry (pictured left) across the Colorado, and renamed Junction City, Rioville. He established a post office with himself as postmaster until his death in 1903. He had a nine-room home built with rock walls two feet thick and a fireplace in each room. His farm contained 320 acres and his ranch extended over the Colorado River 95 miles to the border of Kingman, Arizona. The Mormon pioneers never succeeded in bringing riverboats to the mouth of the

Virgin but Bonelli did. Riverboat captains, of whom Jack Mellon was one of the most famous, brought their steamers to the mouth of the Virgin during high water season where they would unload supplies and depart loaded with salt, fruits, vegetables, and wine.29

Prominent in local educational matters, Bonelli served on the Nevada State Board of Agriculture. He attended the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893 and the San Francisco Mid-Winter Fair in 1894 where he displayed grapes, limes, peaches, and almonds which he had grown at Rioville. He also displayed one-foot square translucent blocks of his famous salt as well as sheets of mica. He served as a voluntary weather observer reporting the daily high and low temperatures to the United States Weather Bureau.

The death of Ute Warren Perkins in the spring of 1903 was an occasion for Bonelli to articulate his philosophy of life in an eloquent letter to the Perkins family:

Out of the unfathomable abyss of eternity come our destinies, thence flow also our hopes and aspirations, and in that realm so far off and yet so near to the human heart and its in most feelings, we alone find the strength to carry our burdens . . . Those who have gone before us in their onward march of progress to a higher class in the school of eternity have found what we are unable to see, and the bitterness of our sorrows will not comfort, hence let it work in us as a purifier only, and it heal as soon as it may be possible.30

The twentieth century brought new changes and challenges. River freight had all but disappeared and the ferry business was almost at a standstill. With a reduced water supply alfalfa did poorly and grape production had all but stopped. Bonelli leased the ferry, his ranch and his holdings for one year, but the operator could not make a profit and Bonelli had to run it again in 1902.

In November 1903 he returned to Pioche where he settled his business and put his affairs in order. Returning to St. Thomas he rested a day with his son Frank and then started for Rioville. En route he apparently suffered a stroke, arriving at Rioville the next day confused and claiming that he had been lost in the hills four or five days. Declining mentally and physically the next few weeks he would pass away on 20 December 1903.

The family honored his request to be buried on a low mesa overlooking his beloved home on the Colorado River. His cherished companion Ann lived for a while with her daughter Alice and son-in-law Joseph F. Perkins in Overton. Upon the death of Alice she moved to Kingman, Arizona, to live with her son George where she died on 19 March 1911.

Unwittingly, the United States Government would rob Bonelli of his final resting place. In 1934, as the government relocated all the graves that would be inundated by the waters of Lake Mead, Bonelli’s remains were disinterred and removed to Kingman, Arizona, where he was buried next to his faithful English bride, Ann Haigh Bonelli.31 Today Lake Mead has buried any evidence that Bonelli ever existed in St. Thomas or at the mouth of the Virgin. In Overton, Nevada, a single street bears his name.

1For a more complete history of Daniel Bonelli, the reader is referred to the author’s longer version, “From Switzerland to the Colorado River: Life Sketch of the Entrepreneurial Daniel Bonelli, the Forgotten Pioneer,” Utah Historical Quarterly, Winter 2006, 74: Number l, 4-23.

2Dr. Melvin T. Smith, former director of the Utah State Historical Society, in conversation with author.

3Walter Lips, “Daniel Bommeli of Bussnang: the Life Story of a Swiss,” translation of a presentation by Walter Lips on September 19, 1997, in Greuterhof, Islikon, Switzerland; hereafter cited as Lips, “Daniel Bonelli of Bussnang.” Hans George, a weaver by trade, also did considerable coopering, making tugs and barrels. Hans George had been married previously to his second wife’s sister, Anna Barbara Ammann, who had died in 1834. The children of the first marriage who survived to adulthood were Johann George and Maria (Mary). From the second marriage the only adult survivors were Johann Daniel, Susann/Suzetta, Elisabeth/Lisette, and Louisa/Louise.

4Dale Z. Kirby, “History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Switzerland,” unpublished Master’s Thesis, Brigham Young University, 1971.

5The articles appeared between 9 April 1859 and 11 August 1860 in the Millennial Star.

6Ross had been a counselor to Asa Calkins in the European Mission Presidency and was in charge of the Saints on the Underwriter. His company was made up largely of those who had been on the ship with him. Daniel had also developed a friendship with Ann Haigh, a twenty-six year old convert who sailed with Daniel on the Underwriter and had been very impressed with Bonelli’s articles published in the Millennial Star. The friendship would later culminate in marriage.

7Johan Georg Bommeli, Translated Journal, 12 March 1850-11 March 1861, copy in author’s possession. Hereafter cited as Bommeli, Translated Journal.

8Karl G. Maeser, President German Home Mission, to Brigham Young, February 1861 and 13 June 1831.

9Daniel Bonelli to President Brigham Young, January 1, 1862. Brigham Young Collection, LDS Church Archives.

10Daniel Bonelli to Apostle George A. Smith, July 18, 1862. Brigham Young Collection, LDS Church Archives.

11The Latter-day Saints Millennial Star, LDS Church Archives, 24:21-22,

12This baby lived but a short time, dying in 1864. Daniel’s wife Ann, in her grief turned to spiritualism and astrology in a vain attempt to communicate with her departed daughter.

13Daniel Leonard, called Leonard to distinguish him from his father died, in 1883 after being bitten by a rattle snake for the third time.

14Married Ross Blakely. She died 26 June 1890.

15Married Effie Tarr on 1 January 1895. Died 26 August 1933.

16Married Joseph Franklin Perkins on 27 March 1904. Died 16 October 1906.

17Diary of Mrs. Albert Perkins, aka Hannah Gold Perkins, LDS Church Archives.

18Daniel Bonelli to Brigham Young, January 19 1862, Brigham Young Collection, LDS Church Archives.

19See Andrew Karl Larson, I Was Called to Dixie (Salt Lake City. Deseret News Press, 1961), 43-54. Nellie Gubler, “History of Santa Clara,” in Under the Dixie Sun, ed. Bernice Bradshaw (Washington County Chapter, Daughters of the Utah Pioneers), 1950, 145-176.

20Daniel Bonelli to the Deseret News, 20 May 1864, LDS Church Archives.

21Deseret News, 29 January 1868.

22Deseret News, 9 April 1868.

23Jackson, a veteran of the Mexican War had married Carolyn Perkins Joyce in 1852 in San Bernardino.

Carolyn came west in 1846 on the ship Brooklyn. After settling in Yerba Buena her husband sought for gold and apostatized. She moved to San Bernardino and married Jackson. A beautiful singer, she was known as the “Mormon Nightingale,” Together with her husband they had one of the largest nurseries in San Bernardino and supplied plants and cuttings to northern as well as southern Utah.

24Deseret News, 27 May 1868.

25Deseret News, 14 April, 1869.

26Warren Foote, Autobiography, 92. LDS Church Archives.

27Record of Members Collection, Santa Clara Ward, Reel 6259, LDS Church Archives.

28Daniel Bonelli to the Pioche Weekly Record, 28 April 1883.

29Richard E. Lingenfelter, Steamboats on the Colorado, River, 1852-1916. (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1978), 53

30Letter in author’s possession. Ute Warren was the author’s great grandfather. Bonelli’s daughter, Alice Maud married Ute Warren’s son, Joseph Franklin.

31Las Vegas Review Journal, 24 November 1934. 6

No comments:

Post a Comment